#本文由作者授权发布,未经作者许可,禁止转载,不代表IPRdaily立场#

来源:IPRdaily中文网(IPRdaily.cn)

作者:Dr Philip Cupitt Partner 麦仕奇英国伯明翰办公室

原标题:欧洲视角:美国专利商标局关于计算机实施的发明的指导意见

2019年1月7日,美国专利商标局(USPTO)发布了两份针对计算机实施的发明的权利要求的主题适格性和清楚性的审查实践的指导意见。在本文中,笔者对USPTO的新指导意见与欧洲专利局(EPO)已确立的做法进行比较,并且提供撰写满足这两个专利局要求的专利申请的实用建议。

主题适格性

关于审查计算机实施的发明的可专利性,EPO拥有长期建立并且一致的做法,其基于多年来逐渐演进的判例法。相反,USPTO在美国法典第35号标题第101条(35 U.S.C. § 101)下审查主题适格性的做法一直不太一致,并且在2014年美国最高法院对于爱丝公司诉CLS银行国际公司(Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International)的判决后,更为动荡。

为了提高USPTO应用§101进行专利申请审查的一致性和可预测性,针对主题适格性的新指导意见确立了以下三“组”专利不适格的“抽象概念”:

a) 数学概念 – 数学关系、数学公式或方程、数学计算;

b) 组织人类活动的某些方法 - 基本的经济原理或实践 (包括对冲、保险、降低风险);商业或法律活动 (包括合约形式的协议;法律义务;广告、市场或销售活动或行为;商业关系);管理人员之间的个人行为或关系或交互(包括社会活动、教学、以及遵守规则或指导)以及

c) 思想过程 - 人脑中进行的观念(包括观察、评估、判断、观点)。

USPTO的新“分组”与欧洲已有四十多年的排除在可专利性之外的主题密切对应。例如,USPTO确立的“数学概念”和“思想过程”分组与欧洲专利公约第52条第2款a和c项(Article 52(2)(a) and (c) EPC)中叙述的排除在可专利性之外的“数学方法”和“用于进行思想行为的方法”相类似。尽管“组织人类活动的某些方法”分组乍一看并不符合欧洲排除在可专利性之外的主题,但USPTO关于此类方法的示例全都涉及EPC第52条第2款c项下作为“商业方法”而被排除在可专利性之外的主题。

我们预期,USPTO关于主题适格性的指导意见将导致USPTO与EPO实践之间更大的分歧。鉴于之前提到的USPTO新“分组”与欧洲现存的排除在可专利性之外的主题之间的相似性,USPTO认为不可专利的大多数发明在欧洲将依旧不可专利。然而,也可能存在某些技术领域根据EPO已建立的做法是不可专利的,却落在USPTO的分组之外。例如,图形用户界面(GUI)在EPO难以获得专利授权,但似乎并未落入USPTO的分组之内。对于此类技术领域,我们预期USPTO会采取比EPO更宽松的做法,由此会进一步增加这两个专利局之间的分歧。

关于“司法例外的实际应用”的权利要求

一个有趣的方面是,主题适格性指导意见针对“司法例外的实际应用”的权利要求,创立了新的安全港。

在USPTO评估主题适格性的测试的第2A步,需要询问一个权利要求是否“针对司法例外”,诸如自然法则、自然现象或抽象概念。如果发现权利要求不是针对司法例外,那么该权利要求就是专利适格的。相反,如果发现权利要求针对司法例外,那么该权利要求有可能被认为是专利不适格的,因此需要进一步对其分析。

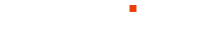

根据主题适格性的指导意见,如果一个权利要求记载了该司法例外的实际应用(参见以下图1),那么该权利要求不能被判定为针对司法例外。也就是说,该权利要求将被认为是专利适格的。

USPTO的指导意见反映了EPO最近关于数学方法的审查实践的变化 ,如EPO在2018年11月版的《审查指南》中所述的那样(参见第G章第II部分第3.3节,( Chapter G-II, 3.3))。在EPO的新实践框架下,如果一个权利要求限定于数学方法的特定“技术应用”,那么该数学方法能对发明的技术特点有贡献。在此情形下,当EPO审查创造性时,数学方法能够与现有技术的区别开来。

当撰写处于专利适格性的边界地带的发明的专利申请时,我们建议描述并要求保护该发明的任何技术应用实例。例如,如果可以想象发明能用于控制特定的技术系统(例如工业过程、或通用计算机之外的装置)、测量物理特征、或优化数据通信或存储,那么这些就应该公开。以此方式撰写的申请,通过将权利要求限定于发明的特定应用实例,将提供克服美国§101异议或欧洲创造性异议的可能性。

功能性权利要求语言

十分常见的是,针对计算机实施的发明的权利要求包括功能性语言,诸如“用于执行X的手段”。

在欧洲,使用功能性语言常常是撰写权利要求的最简单方法,这样的撰写能够覆盖一些软件实现的发明的所有实现方式。使用功能性权利要求语言也为EPO的《审查指南》所允许(例如第F章第IV部分第3.9.1节(Chapter F-IV, 3.9.1)),从中可见对于实践中常见的不同类型措辞(例如,“用于……的手段”、“适于……”、“配置成……”等等)并无特殊偏好。

然而,长期以来,功能性权利要求语言在美国都存在问题。在美国法典第35号标题第112条f项(35 U.S.C. § 112(f) )下,一个权利要求如果记载了用于执行一功能的“手段”或“步骤”,但是没有记载执行该功能的结构,则会被理解为覆盖了说明书中描述的结构(以及其任何等同)。因此,尽管功能性权利要求语言在欧洲通常具有宽的保护范围,但是在美国的保护范围可能窄得多。

在撰写权利要求时应当避免使用哪些功能性术语方面,USPTO关于清楚性的指导意见提供了有益的建议。除了避免在§112(f)提到的“手段”和“步骤”之外,其他应避免的术语包括:

“用于……的机构”、“用于……的模块”、“用于……的设备”、“用于……的单元”、“用于……的部件”、“用于……的元件”、“用于……的元件”、“用于……的装置” 、“用于……的机器”、和“用于……的系统”。

然而,该指导意见指出,并不存在必然导致根据§112(f)解释的权利要求的固定术语列表,也不存在必然避免如此解释的固定术语列表。

当撰写权利要求时,我们建议谨慎使用功能性语言。在合适的情况下,应考虑使用指示结构性限定的术语。例如,权利要求术语“用于计算的手段”可替换表述为“处理器,配置成计算”。后者的表述范围更宽,并且在美国和欧洲都能被接受。为了保持在欧洲使用更广泛的功能性语言的选项,说明书的“发明概要”部分可包括使用“用于……的手段”语言描述的附加发明声明。

公开内容

关于清楚性的指导意见还强调确保专利说明书包含发明的完整公开的重要性。

在欧洲,专利说明书需要以足够清楚和完整地公开发明内容以使得本领域技术人员能实现发明(欧洲专利公约第83条和第100条b款(Articles 83 and 100(b) EPC))。未能满足该要求是专利申请被驳回或撤销的一个理由。然而,实际上EPO很少基于该理由驳回针对计算机实施的发明的专利申请或撤销此类专利。

尽管EPO的审查方法对专利撰写者施加的要求极少,USPTO关于清楚性的指导意见提醒撰写者注意,在撰写要在美国提交的计算机实施的发明的专利申请时,说明书应公开用于执行要求保护的功能的算法。就此而言,指导意见将算法定义为“用于解决逻辑或数学问题或执行任务的有限步骤序列”。

算法可被表达为数学公式、文字、流程图、或其他任何适当的形式。应谨慎确保所公开的算法足以执行要求保护的所有功能。未能公开算法可导致美国专利或申请的权利要求在美国法典第35号标题第112条b项(35 U.S.C. § 112(b))下被认为是不确定的,并且在美国法典第35号标题第112条a项(35 U.S.C. § 112(a) )下被认为是缺乏书面说明。

通常,我们建议通过(附图中的)流程图和流程图的每一步骤的详细书面说明的结合来提供关于算法的所需公开。至少,流程图应包括对应于独立方法权利要求的每一步的步骤。理想情况下,流程图还应包括对应于从属权利要求的每一步的步骤,但是,为了在EPO中允许更多的修改灵活性,说明书应清楚指出哪些步骤是可选的。

附注/Notes:

美国专利商标局针对计算机实施的发明的权利要求的主题适格性和清楚性的审查实践的指导意见(英文),见以下链接:

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/07/2018-28282/2019-revised-patent-subject-matter-eligibility-guidance;

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/07/2018-28283/examining-computer-implemented-functional-claim-limitations-for-compliance-with-35-usc-112

附:英文全文

A European View of the USPTO's Guidance

on Computer-Implemented Inventions

On 7 January 2019, the United States Patent and Trademark Office ("USPTO") published two guidance notes on its practice for examining subject matter eligibility and clarity of claims for computer implemented inventions. In this article, we compare the USPTO's new guidance with the established practice of the European Patent Office ("EPO"), and provide practical suggestions for drafting patent applications that will satisfy the requirements of both patent offices.

Subject Matter Eligibility

The EPO has a long-established and consistent practice for examining the patentability of computer-implemented inventions, which is based on a body of case law that has evolved gradually over many decades. In contrast, the USPTO's practice for examining subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 has been less consistent, and has seen particular upheaval following the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International in 2014.

In order to improve the consistency and predictability of the USPTO’s application of § 101, the new guidance on subject matter eligibility identifies the following three "groupings" of patent ineligible "abstract ideas":

a) Mathematical concepts – mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, mathematical calculations;

b) Certain methods of organizing human activity – fundamental economic principles or practices (including hedging, insurance, mitigating risk); commercial or legal interactions (including agreements in the form of contracts; legal obligations; advertising, marketing or sales activities or behaviors; business relations); managing personal behavior or relationships or interactions between people (including social activities, teaching, and following rules or instructions); and

c) Mental processes – concepts performed in the human mind (including an observation, evaluation, judgment, opinion).

The USPTO's new "groupings" closely correspond to some of the exclusions from patentability that have existed in Europe for over forty years. For example, the "mathematical concepts" and "mental processes" groupings identified by the USPTO are similar to the exclusions on "mathematical methods" and "methods for performing mental acts" that are set out in Article 52(2)(a) and (c) EPC. Although the "certain methods of organizing human activity" grouping does not at first glance correspond to one of the European exclusions, the USPTO's examples of such methods all relate to subject matter that would be excluded from patentability In Europe as being a "method for doing business" under Article 52(2)(c) EPC.

We anticipate that the USPTO's guidance on subject matter eligibility will lead to a greater divergence between USPTO and EPO practice. In view of the previously-mentioned similarities between the USPTO's new "groupings" and the existing exclusions in Europe, most inventions that are found to be unpatentable by the USPTO will continue to be unpatentable in Europe. However, there are likely to be areas of technology that are unpatentable in accordance with the EPO's established practice, but which fall outside the USPTO's groupings. For example, graphical user interfaces (GUIs) are difficult to patent at the EPO, but seem not to be covered by the USPTO’s groupings. For those areas of technology, we expect the USPTO to adopt a more permissive approach than the EPO, thus increasing the divergence of the two offices' practices.

Claims for a "Practical Application of a Judicial Exception"

An interesting aspect of the guidance on subject matter eligibility is the creation of a new safe harbour for claims directed to a "practical application of a judicial exception".

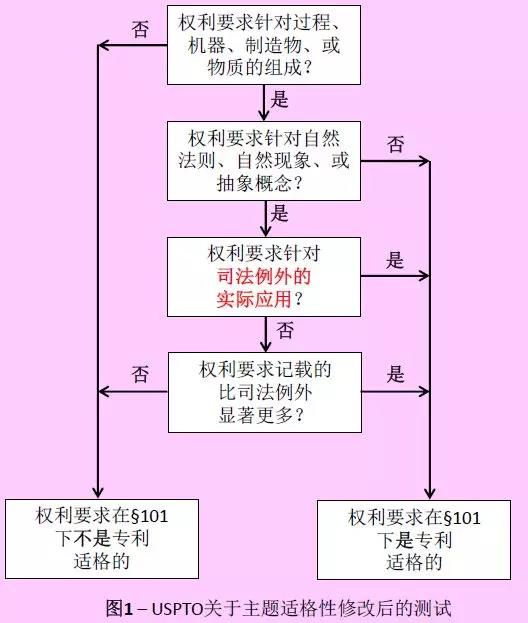

In Step 2A of the USPTO's test for assessing subject matter eligibility, it is necessary to ask whether a claim is "directed to a judicial exception", such as a law of nature, a natural phenomenon or an abstract idea. The claim is patent eligible if it is found not to be directed to a judicial exception. Conversely, further analysis of the claim is needed if it is found to be directed to a judicial exception, with the possibility that the claim will be deemed patent ineligible.

In accordance with the guidance on subject matter eligibility, a claim is judged not to be directed to a judicial exception if the claim recites a practical application of that judicial exception (see Figure 1, below). The claim is thus found to be patent eligible.

The USPTO’s guidance mirrors recent changes to the EPO’s practice for examining mathematical methods, as set out in the November 2018 edition of the Guidelines for Examination in the EPO (Chapter G-II, 3.3). Under the EPO’s new practice, a mathematical method can contribute to the technical character of an invention if the claim is limited to a specific “technical application” of the mathematical method. In this case, the mathematical method is capable of distinguishing over the prior art when inventive step is examined by the EPO.

When drafting patent applications for inventions on the borderline of patent eligibility, we suggest that any technical use cases of the invention are described and claimed. For example, if the invention could conceivably be used to control a specific technical system (such as an industrial process, or a device other than a general purpose computer), measure a physical property, or optimise the communication or storage of data, then this should be disclosed. Drafting the application in this manner will provide a possibility of overcoming a § 101 rejection in the U.S., or an inventive step

objection in Europe, by limiting the claims to a specific use case of the invention.

Functional Claim Language

It is common for claims for computer-implemented inventions to include functional language, such as “means for performing X”.

In Europe, the use of functional language is often the simplest way to draft claims that cover all of the many ways in which some inventions can be implemented in software. The use of functional claim language is permitted by the Guidelines for Examination in the EPO (Chapter F-IV, 3.9.1), which notes that there is no particular preference among

the different types of wording that are commonly seen in practice (e.g. “means for”, “adapted to”, “configured to”, etc.).

However, it has long been the case that functional claim language is problematic in the US. Under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f), a claim that recites a “means” or “step” for performing a function, but without reciting the structure that performs that function, is construed to cover the structure that is described in the specification (and any equivalents thereof). Thus, whereas functional claim language typically has a broad scope in Europe, it can have a much a narrower scope in the U.S.

The USPTO’s guidance on clarity provides helpful suggestions on functional terms that should be avoided when drafting claims. In addition to avoiding the words “means” and “step” that are mentioned in § 112(f) itself, other terms to avoid include:

“mechanism for”, “module for”, “device for”, “unit for”, “component for”, “element for”, “member for”, “apparatus for”, “machine for” and “system for”.

However, the guidance points out that there is no fixed list of terms that will always result in a claim being interpreted in accordance with § 112(f), nor is there a fixed list of terms that will always avoid such interpretation.

When drafting claims, we suggest that functional language is used with care. Where appropriate, one should consider using terminology that implies a structural limitation. For example, the claim term "means for calculating" could alternatively be expressed as "a processor configured to calculate". The latter wording is broad, yet should be acceptable in both the U.S. and Europe. To keep open the option to use broader functional language in Europe, the "Summary" section of the description could include additional statements of invention that use "means for" language.

Content of the Disclosure

The guidance on clarity also emphasises the importance of ensuring that a patent specification contains a complete disclosure of the invention.

In Europe, it is necessary for the patent specification to disclose the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art (Articles 83 and 100(b) EPC). Failure to comply with this requirement is a ground for refusing an application or revoking a patent. In practice, however, it is rare for the EPO to invoke this ground when refusing applications, or revoking patents, for computer-implemented inventions.

Whereas the EPO's approach to examination places very few requirements on the draftsperson, the USPTO's guidance on clarity is a reminder that, when drafting a patent application for a computer-implemented invention that will be filed in the U.S., the specification should disclose an algorithm for performing the claimed functionality. In this regard, the guidance defines an algorithm as "a finite sequence of steps for solving a logical or mathematical problem or performing a task".

The algorithm may be expressed as a mathematical formula, as prose, as a flow chart, or in any other suitable manner. Care should be taken to ensure that the disclosed algorithm is sufficient to perform all of the functionality that is claimed. Failure to disclose an algorithm can result in claims of the U.S. patent or application being found to be indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112(b) and lacking written description under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a).

In general, we suggest providing the necessary disclosure of the algorithm through a combination of a flow chart (in the drawings) and a detailed written description of each step of the flow chart. At the very least, the flow chart should include a step corresponding to each step of the independent method claim(s). The flow chart should ideally also include a step corresponding to each step of the dependent method claims but, to allow more flexibility for amendment at the EPO, the description should make clear which steps are optional.

来源:IPRdaily中文网(IPRdaily.cn)

作者:Dr Philip Cupitt Partner 麦仕奇英国伯明翰办公室

编辑:IPRdaily赵珍 校对:IPRdaily纵横君

“投稿”请投邮箱“iprdaily@163.com”

「关于IPRdaily」

IPRdaily成立于2014年,是全球影响力的知识产权媒体+产业服务平台,致力于连接全球知识产权人,用户汇聚了中国、美国、德国、俄罗斯、以色列、澳大利亚、新加坡、日本、韩国等15个国家和地区的高科技公司、成长型科技企业IP高管、研发人员、法务、政府机构、律所、事务所、科研院校等全球近50多万产业用户(国内25万+海外30万);同时拥有近百万条高质量的技术资源+专利资源,通过媒体构建全球知识产权资产信息第一入口。2016年获启赋资本领投和天使汇跟投的Pre-A轮融资。

(英文官网:iprdaily.com 中文官网:iprdaily.cn)

本文来自IPRdaily.cn 中文网并经IPRdaily.cn中文网编辑。转载此文章须经权利人同意,并附上出处与作者信息。文章不代表IPRdaily.cn立场,如若转载,请注明出处:“http://www.iprdaily.cn/”

共发表文章

31245篇

共发表文章

31245篇- 我也说两句

- 还可以输入140个字